Csíksomlyói passió by the National Theatre in Budapest premiered in the Csíksomlyó mountain saddle on August 18, 2018. This version of the production, transformed for an open space and expanded with local folk dance ensembles and choirs, was seen by 25,000 spectators. The following National Theatre colleagues were asked about this large-scale enterprise by Mária Rádió editor Vera Prontvai: Zsolt Szász, the dramaturg of the theatre performance; Edit Ágota Kulcsár, the production manager of the performance in Csíksomlyó; and poet Ágnes Pálfi. (For the discussion in Hungarian see: Szcenárium, October 2018, pp. 14–28.)

V. P.: Warm greetings to Ágnes Pálfi, Edit Kulcsár and Zsolt Szász in the studio of Mária Rádió. Can you tell me what specific role each of you played in the creation of this large-scale endeavour?

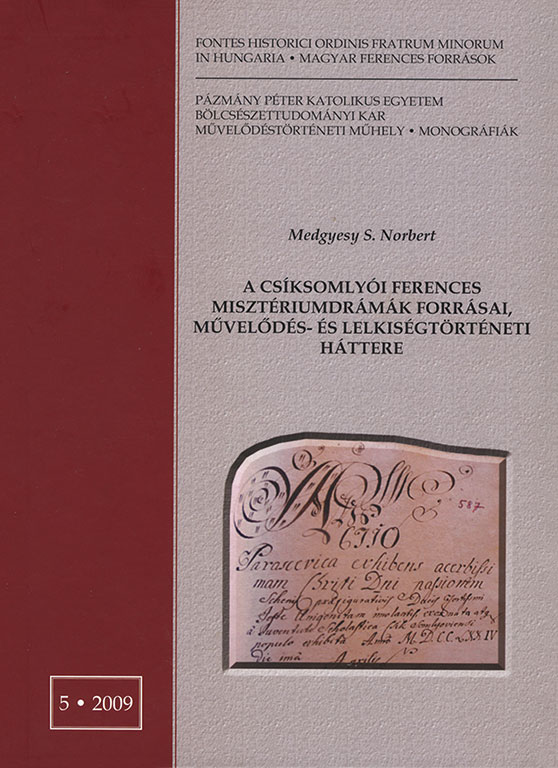

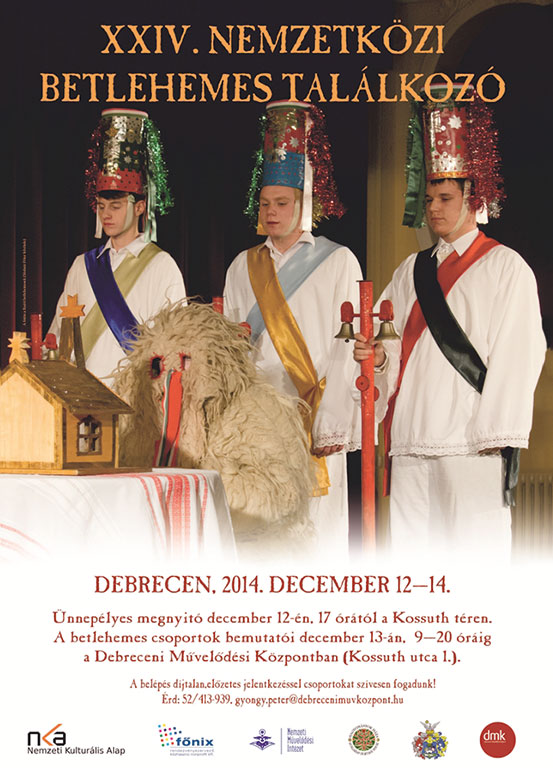

Zs. Sz.: Well, I’ll start by answering as the dramaturg of the theatrical version which opened on March 9th, 2017. I thought it was important to tell in the text promoting this performance that we’re now in the third era of 20th century adaptations of school dramas from Csíksomlyó as well as passion plays in general.[1] Director Attila Vidnyánszky’s present enterprise could rely on academic results that were previously unavailable, such as, in the first place, the book[2] written and edited by Norbert S. Medgyesy, which includes a complete analysis of passion play texts based on the findings[3] of a research group led by István Kilián. With respect to archaic folk prayers, I’d also like to draw attention to the summary work[4] by Zsuzsanna Erdélyi, who, after editing her famous collection of prayers (Hegyet hágék, lőtőt lépék) also explored the genesis of tradition as well as folk religious texts, and collated them with Franciscan traditions in terms of spirituality, which means she looked into the antecedents philologically, too. Additionally, we could draw on the fact that significant dance companies with their roots in the folk dance house tradition such as our creative partner, the Hungarian National Dance Ensemble, not only reach out with proper depth and attention to detail for authentic dance language today, but turn to related ritual elements, traditional games and religious folk practices in the same way. So we can speak of a kind of synthesis. In fact, I was the one who had access to the scientific mapping of the topic, so maybe that’s why I was selected as the dramaturg of the production. From 1990 on, with my former theatre groups (MéG Színház [MéG Theatre], Hattyúdal Színház [Swan Song Theatre]), we were into staging dramatic or semi-dramatic texts which were preserved in the chronicle tradition, like for example in the codices. Therefore I also had acting experience in this area. In 1991 we took on a mission together with theatre historian and dramaturg Márta Tömöry, namely the mapping and presentation of betlehemezés (Hungarian nativity plays), which is a distinguished genre of the sacred dramatic play tradition still alive in the Carpathian Basin, besides the organization of the annual Nemzetközi Betlehemes Találkozó (International Betlehemes [Nativity Play] Meetings). Now we have hundreds of hours of video footage, which was of great help in terms of tone and rendition during the rehearsals of the Csíksomlyói Passió. It served as an example of how to authentically perform these old texts with a spiritual-intellectual-religious charge today.

V. P.: How did the others get involved in this process?

Á. P.: To be honest, I don’t even remember the moment when I had a conversation with Zsolt and the thought occurred to me that it would be worth associating contemporary literature with the school drama texts as well as the sacred songs that András Berecz sings in the performance, drawing from his own collections, too. If I remember correctly, the work started in June 2016 with us listening to these songs in Attila Vidnyánszky’s office. And when we put together a possible script for Attila from the texts of the school plays during the summer, in August, Zsolt and I started looking for contemporary literary parallels. And suddenly I remembered Géza Szőcs’s Passió (Passion), which had a profound impression on me at the very beginning of the 2000s when I got the book from Márta Tömöry. After reading the slender book, both of us were immediately enlightened that this was the text that we should give to Attila. Because, knowing his “fragmentary dramaturgy”, we stumbled upon incredible parallels in it and discovered the same perspective as Attila uses in composing his stage works. Passió by Géza Szőcs is a postmodern venture, in terms of both its texts and as a whole. All the hallmarks of this contemporary trend can be discovered in it: it contains adaptations, guest texts, at least two dozen biblical and literary quotes, often with footnotes. Furthermore, it also names literary historical and philosophical sources, such as the serious theoretical work of Gyula Rugási. The reader of the book experiences two things at the same time: on the one hand, Géza Szőcs is at home in this postmodern way of thinking, and on the other hand, the framework of the composition is very firmly provided by the biblical story. Most of the texts are rewritings of the biblical one; sometimes through literary allusions, when the author emphasizes that his predecessors have already touched on the subject, and thus he can rely on their texts; but there are also completely new entries, with his own poetic ingenuity also present from time to time. And he is able to maintain these two things in balance in such a way that it results in a remarkable and exceptional philosophical achievement, too. For me, it demonstrates that the biblical framework, the dimension of salvation history, can perfectly be reconciled with the postmodern approach, and that contemporary artists of a truly high calibre are not interested in obliterating the foundation of the Christian cult community by replacing the existential philosophical surplus of the Passion of Christ. For me, this biblical framework makes the real benefits of postmodernism much more tangible and comprehensible. The Easter tradition, the Passion of Christ, which we experience anew every year, can safely be collated with the postmodern aesthetic creed that there is nothing new under the sun, that everything has already happened before. If you give some thought to it, this view is essentially no different from that of the salvation history in the biblical tradition.

V. P.: Edit, at which point did you get involved in this creative process?

E. K.: I got involved in the work when Attila Vidnyánszky decided to take the National Theatre production, which was created together with the Hungarian National Dance Ensemble, to the mountain saddle of Csíksomlyó. He invited me when the initial steps of this bold venture were taking place. It wasn’t just about going there and nailing a performance. It was a very serious commitment, as local actors were also involved in the production. My job was to connect the threads between people. Our technicians also needed very serious preparation, and we had to find those local partners who could be of help. We had three days to put the performance in a completely different space in the mountain saddle and to create an acceptable production, and what’s more, there were more guest performers than there were of us. Our fifty dancers were joined by another hundred, and our twenty-something actors were joined by a fifty-person children’s choir. The basic idea was not just taking something there but cooperation; we wanted to co-create the performance, together.

V. P.: The concept of postmodernism has been mentioned here. This direction can also be called postmodern, as there are many indicators of this. How can that be reconciled with passion plays?

Zs. Sz.: In my opinion, Géza Balogh wrote the best review of the National Theatre performance in Criticai Lapok (Critical Pages). He talks about how we are not in a small, isolated place, because the bay-shaped stage has a grand embrace. Thus the 190 viewers, who are a relatively small number, become real participants in the action as they are watching the stone theatre version together. Imagine a U-shaped space, with the viewers sitting in the centre. If we talk about postmodernism and try to associate Attila Vidnyánszky’s theatre with it in a descriptive way, mention must be made of the multiple parallel events, multiple layers of meaning appearing on his stage, which guarantee communication with the recipient at all levels of the senses. This, if you will, means being outside of space and time in contrast to the realism of linear plot structuring. It is as if all sounds, images, and physical actions were swirling together in one space, much like how a modern person’s mind can hold multiple thoughts at once. In other words, it is as Ágnes has also talked about: there are various layers of meaning that move together. All the consequences, intellectual and material implications of the continuous two-thousand-year-old narrative are present at the same time. What’s interesting here though is that, within this pile, Attila was still able to make the Passion story itself unfold linearly. In the Bible, the four Evangelists describe this story from different perspectives, in different ways, with different attitudes, yet these narratives have the same nodes from Palm Sunday to the Resurrection and beyond, as the story does not end on Good Friday, nor even on Easter Sunday, but we reach Pentecost and even beyond, Mary’s Assumption. If we take into account the period opposite the middle of August in the annual cycle with the January wedding at Cana, we find that a kind of heavenly wedding is the end of the story.

Á. P.: To this I would add that Géza Szőcs, apparently due to the characteristics of poetic language, does not follow the linear sequence of events in his Passió. The best example of this is that Mary’s prayer comes much earlier than the event of the death on the cross. The timeline is in fact reversed, as if the event which we’ll zoom in on later had already taken place, showing what I’ve already pointed out, that Easter is actually about the death of Jesus on the cross happening to us over and over again. This act of remembrance is different from the Christmas mystery which Zsolt has also mentioned. The tradition of betlehemezés (Nativity playing) involves letting Mary and the holy family into our home, so that by giving them accommodation, we break the resistance of our ancestors. The act of acceptance, the birth of Jesus as the resolution of dramatic tension is repeated year by year through the betlehemes, whereas the Easter Passion continues to address Jesus’ drama ending with his death on the cross, and regenerates it year after year. Confronting this, or repentance, does not provide absolution. Although its possibility is always there, it never really happens, as in the case of the Christmas birth. I’d also add that Attila finishes the performance with Christmas carols, which means that the story ends with the birth of Christ, that is comes full circle, and we return to its beginning. Interestingly, the wedding at Cana also appears in Géza Szőcs’s text, which prefigures the second coming of Christ. This is also probably related to the characteristic of poetry, since a poetic text does not need to be objectified in the same way as a stage play. Time and space are handled with a lot more freedom in poetry. I should also mention that this text has been adapted several times, for example, there was an oratorio version at the Merlin Theatre. And on our way to the studio, Zsolt and I were talking about whether it would probably be the best to make a radio play out of it.

as illustration in Géza Szőcs’s book Passió (Magvető, 1999)

Zs. Sz.: In the case of playing the Passion story the central issue is definitely authenticity, and it is so from two aspects: the first one is the faith we start with, which in theatre is not necessarily a question of religiosity. In my opinion, we’ve won the battle in this regard because the knowledge that Zoltán Kodály called attention to in connection with the folk song, that is, if we want to sing the folk song at a native language level then we must learn the language of the 18th century, has already become second nature to Zoltán Zsuráfszky’s dancers. These dancers don’t just perform choreographies and don’t just sing, but they also speak this 18th century text, the text of school dramas at a native language level. So the myth that this archaic text cannot be performed authentically has been dispelled by this. This high level of quality, which by the way characterizes our modern folk dance culture in general, has greatly contributed to the authenticity of the drama taking place on the stage. It’s also worth bringing up András Berecz in this regard. Ágnes has already remarked that the twelve sacred hymns being sung belong to the archaic layer of religious folk songs. In fact, the entire medieval tradition of Franciscan spirituality is inherent in the image-making of these songs. Some of these were collected by András Berecz himself in Moldavia and Székelyföld (Székely Land), where he as a regular participant at the pilgrimage of Csíksomlyó met in person the singers for whom these songs are real prayers. Besides the dancers’, this kind of initiation is the other source of authenticity on the stage. To this is added the treasure of folk tales which András Berecz partly collected and transcribed into his vernacular. He renders them in the oldest possible symbolic visual language, showing the world view cultivated by the Hungarian folk spirit virtually in its ontogenesis, from the creation of the world – an indispensable element of which is the humour of the performance. All of this certainly underpinned the theatrical authenticity. My idea of screening the one-hour bethlehemes mystery play from Szentegyházasfalu to Attila Vidnyánszky and the actors before the first full rehearsal also worked well. I wanted to demonstrate by this that this mode of speech still exists in folk practice and that this consciously cultivated “technique” can be learned by professional actors as well.

(photo by Katalin Balázs, source: szekelyhon.ro)

Á. P.: During the rehearsals and now in the version performed in the mountain saddle, we observed that the actors were increasingly catching up with this kind of speech, which as we already saw during the first rehearsals was not at all a problem for the dancers. It was one of the big surprises for us to see how the actors began to tune into this wavelength, and they brought it to such a high level of proficiency that their speech was already unified in the saddle.

Zs. Sz.: Furthermore, the speech could be considered overwhelmingly powerful. Especially in the text commonly referred to as the Aranymiatyánk (Golden Lord’s Prayer) which recounts the events from Palm Sunday to Pentecost. This is a medieval genre, showing a half-dramatic situation of the liturgical drama live, with huge and sweeping power. When the three hundred-strong cast mentioned by Edit speaks, it’s irresistible…

V. P.: To what extent could the dramaturgy of the performance be followed in the outdoor space?

E. K.: The audience breathed so much along with the performance that there were no surprises for them on how to interpret it all. It surely helped a lot that, even though the faces were very far away in this huge space, two projectors showed the production in large and close-up, and the viewers could see the actors’ faces clearly. A state of inspiration was created between performers and spectators, a high level of togetherness that is rarely experienced. I also went out into the audience, because I felt like I wanted to be there. As the first folk religious song began, someone in front of me said it was Mass and stood up. Then ten thousand people stood up, and they were still standing an hour later. The performance touched something within them which was incredible. These people were mainly local residents with religious life being so much a part of their everyday life that they had a clear desire to experience this story. They listened to the whole thing as if it was a mass. I was completely amazed by this phenomenon, the way those ten thousand people stood up because they felt that this could only be listened to standing…

V. P.: And in complete silence…

E. K.: Yes, in complete silence. The wording may sound a bit naive compared to my colleagues’ brainstorming, but let me read something out. The leader and soul of the Marosszéki Kodály Zoltán Children’s Choir, Sister Éva Vera Nagy, wrote us a report about how they, the members of the children’s choir, saw this event. I don’t think I could phrase what happened there as beautifully as she did. I will read out how they saw our side: “The sincere dedication and exposure of the actors and directors made their creed credible, and triggered the flow of goodness, which brought those on the mountain together as a community in catharsis.” I would add that we really felt for three days that love was growing within us. I can’t find better words for it. We wanted to embrace each other at the end of the performance, and carried that feeling with us further. I would like to utter one more word: blessing. I must say there was a blessing on us, and this was felt more and more each day by everyone: it was only thanks to this that the performance was created with such cooperation, in such a great way, and without any conflicts in this amount of time…We felt the help of the heavens, the protection of this event so to say. I would like to read another part of Sister Vera’s report, because it also shows how the interpretation of this complex text became so simple there: “The Father and the Son were present in the Csíksomlyói Passió. We experienced it a bit like the children were the Holy Spirit. But on further reflection, the Wanderer, with his tales and songs resolving the situations and stopping the events, just like an aria in an opera, is also a representation of the Holy Spirit. Moreover, all the people, the entire audience, received the role of the Holy Spirit in the performance. The profound silence, the striking common song as a reaction.”

Zs. Sz.: The textus, the text of the school dramas has been preserved by some miracle. Árpád Fülöp was the first to publish some of it in 1897. This was the basis for all previous stage adaptations. In 1980, during a restoration, 1800 folios were found from the plinth of the devotional statue of the Virgin Mary, which are the text material for school dramas known today. It was published as a monograph by the research group led by István Kilián after several decades of work. S. Norbert Medgyesi pursued the history of influence as well, and attempted to trace how the original mode of acting, or acting tradition continued, or may have continued. Since there was no film recording in the 18th and 19th centuries, or even in the first half of the 20th century, we can only make assumptions about the mode of acting. What I have experienced during the thirty years of the betlehemes meetings is that in the Csík Basin in the Székely community homogenous mystery play-like long betlehemes have survived, whose text panels, i.e. the constant elements recurring in the scenes, are very similar to these 18th century written school dramas. At the same time, the 42 Passion plays differ from each other in many respects, not only in their verse, but also in their choice of perspective. Don’t think that there is a single final text, developed and canonized in the Middle Ages, which we adopted from Western Europe. What becomes interesting is how the mystery can be brought closer through the Passion of Christ, from era to era, from person to person, and possibly even with regard to the particular student youth. I’ll give you an example: there’s a piece even in the collection of four already, published by Árpád Fülöp, that describes the story in the form of trees talking and competing. In this, the Babylonian cedar knows the royal surplus which, if we continue to think about it, is at the same time Christ’s tree of the cross and the tree of life, bearing everything in its very meaning. Such extreme solutions, or, if you like, very modern approaches exist in this era, too. Returning to betlehemes, I assume that this text- and acting tradition can only come from Csíksomlyó. I even believe to have found evidence for this in the case of Szentegyháza, when I say that not only the Christmas mystery play has survived there, but also the so-called “ördögbetlehemes” (“Devil Nativity”), which is a story of Lazarus. Death and devils appear in it, so the late-baroque mode of acting that can be traced back to the Middle Ages is also palpable. Thus there’s something to draw from, now not only in singing and folk dance culture, but but also in the living tradition of school dramas today.

(source: Magyar Ferences Források 5. Piliscsaba–Budapest, 2009)

V. P.: Connecting to the idea that betlehemes is better accepted by people, this performance also ended with the theme that we’re all redeemed. This is what the creators tried to instill in the souls of those present. Do you see it that way, too?

Zs. Sz.: Although the production was not overadvertised, as I can see from the reports, the majority of the audience was recruited from the Csík basin, and the pilgrimatic, cross-bearing population of villages made a pilgrimage to see the performance.

E. K.: Well, yes, because you had to come over the mountain, you had to make a pilgrimage. Those who were curious about this must have had the same desire as makes them set out on a pilgrimage at Pentecost as well, to experience the power of the Holy Spirit, which is said to dwell here. I feel that the audience was involved in this story with such dignity that a closed circuit was created between them and the performers. It all felt so natural, as is rarely given. Moreover, the postmodern theatre play has turned into a real ceremony in a location where holy masses are held at other times. Let’s not forget that this is a Székely story, so the actor who later plays Christ appears as a Székely lad in Székely clothing from the first moment. The circle closes this way, too, since the viewer sees themselves and their own story, which increases the intimacy of being together. We were anxious for the Csíksomlyói Passió to find its way home. Even so, we were worried not only whether the audience but also whether the place itself would accept our endeavour, and it’s a great feeling that it did. We didn’t dare to hope that it would finally be received with such a blessing. Even the weather was with us.

V. P.: Since the premiere, I’ve been wondering about the question: what could be the message of hammering the nail into the bread at the end of the play?

Zs. Sz.: It doesn’t appear at the end of the production, but before the end, at the most prominent moment. Dénes Farkas, who personifies the dark forces of Lucifer, Satan and the merchant, hammers into the bread the particular fourth nail of which András Berecz speaks earlier in the tale of the gypsy blacksmith. At one point, Attila – and this is his directorial invention – condensed all three symbolic planes of the story into one gesture. What are these? The symbolism of bread – life, tree of the cross – tree of life may be considered well-known. In Berecz’s interpretation, the tale about the fourth nail is less like that: this nail is forever glowing, it can never cool down, so, as I see it, it symbolizes never-ending pain. And this extremely powerful, or, if you like, harsh gesture takes place at the table of the Last Supper. However, this brutality is immediately resolved by our pilgrim uncle called Vándor (Wanderer), who breaks this bread with love and shares it with those nearby. As I see it in the recording, this gesture also worked in the Csíksomlyó mountain saddle. A few loaves of bread are passed out to the spectators, and in no time everybody is singing Boldogasszony anyánk (Our Blessed Mother) together… I’m bringing up this example because you cannot expect the same effect mechanism in a stone theatre and in an outdoor setting. Signal formation works completely differently in such a large space. The cosmic scale is already present in the Csíksomlyó mountain saddle, while it needs to be generated inside a closed space. While on the National stage even a tone or gesture can have a symbolic meaning, this kind of concentrated space and time cannot be created in such a large space. It’s an interesting question how the field of meaning and symbolism developed in the interior space can be transferred without damage to such a large space, how the script and text corpus operating there can be used. Attila Vidnyánszky divided the space into three parts: the altar was in the centre, where every action starts and returns, with the city, the sinful city of Jerusalem with the procurator on the left side, and the site of the crucifixion, Golgotha on the right side.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

E. K.: I’d read another part of Sister Vera’s text: “Our choir members arrived around the monologue of Mary with a mission-driven empathy, in which it was clear that this is not theatre, but this is life. Naturally, the sincere feelings of the protagonists played a huge role in this experience. The emotions flowed so freely towards the children that it was easy for them to imagine the characters in their own family, village, and world. The comforting gesture of the little six-year-old Andika was addressed to both Mary and the actress Auguszta Tóth, who became one for us during the play.”

V. P.: In preparation for the conversation, Zsolt asked me to play in the radio the excerpt “Maria speaks to the saints” from Géza Szőcs’s Passió, performed by Auguszta Tóth. Why did you consider this important?

Zs. Sz.: I would like to pass this question on to Ágnes, who has more experience with the theme of the Mary cult.

Á. P.: Previously, I mentioned that Géza Szőcs places Mary’s prayer a lot earlier. It helps you understand that this is about reliving a past event. In this monologue, a question is posed, which doesn’t receive an answer, however, this condition, this open and personal nature of the question, and the representation of motherhood are so direct as an experience that the dilemma of “what am I bringing my child into this world for” becomes clear for everyone. The text doesn’t move, no answer comes, but this repeated question will be the one that permeates the spirit of the entire Passió. But it’s not just Mary, all the other characters are also on a journey. You asked the question, is there redemption, are we redeemed? Edit put it well when she said we’re on the way. This “being on the road” is in fact the prelude to redemption. It could also be said that what we are in is an Advent spirit and state that carries the promise of redemption. The manifestation of Satan is also very important when he asks: Will Christ redeem me as well? This is embedded in a very strange text-context that plays with the contrast between “money changer” and “redeemer” [5]. Yet in this scene, Satan gets to the point of understanding what this is all about and poses this question. With regard to the bread and the symbolism of him beating the nail into it, I’d like to draw attention to one thing. If we compare the figure of Satan with Pilate, I see this as a gesture of absolute commitment. Because someone has to acknowledge that they are the one who committed the crime. I have to admit that it was a sinful act. At the same time, this gesture also involves that I’m part of something that I already know points beyond. Murder is not the ultimate meaning of Christ’s death. This reminds me of an astonishing remark made by a contemporary poet about what kind of religion it is that puts a murder in the shop window. Another contemporary poet says that Christianity is a humourless religion. These two unjust accusations have come to my mind. Yet, there is no lack of humour in this performance, either.For example, the scene in which Satan has come closer to the essence of salvation than Pilate, who is only concerned with how this story will benefit him and if his name will be remembered. Pilate refuses to accept liability as the primary person responsible for condemning Christ. The act of hammering in the nail is a very radical gesture from Attila on the stage: since bread is nothing other than the body of Christ, with this gesture Satan repeats the act of crucifixion and takes it upon himself.

V. P.: And this is complemented by the gesture that those present will receive a piece of this bread afterwards.

Á. P.: Yes, this is the participation I was referring to earlier. So that at Easter time we always become part of this event which is both scandalous – as Pilinszky says – and pointing far beyond it, forming the foundation of our entire culture. Many don’t know that the apocalypse takes effect when Christ is born (or according to others, when he is baptized). Either way, we stepped into our own time in the life of Christ. And the same thing has in fact been happening since then, the same Easter mystery is repeated with us and through us.

V. P.: Considering the reception of Vidnyánszky’s works, where does this performance fit in?

Zs. Sz.: I’m sure that this is not just another work of art among the many of Attila Vidnyánszky’s previous productions, but also a kind of testimony in terms of faith. Professionally speaking, it’s an extraordinary test of whether the skillset he has used so far is suitable for this testimony. If you like, this performance is the “stress test” of his previous life’s work. According to the crème de la crème, as an artist moves forward on their career path, especially if they are successful, it becomes increasingly difficult to create the next piece.

V. P.: I was thinking during the performance, is it still possible for him to make theatre after this?

E. K.: Of course it is, precisely because it’s both a recharge and a confirmation. Of course, it’s not easy to move on after such a successful performance. I spoke to some who watched it on TV and they said that they also had a cathartic experience through the screen. Then I thought, yes, this was the confirmation of a journey, of an aspiration. At the same time, it’s also a starting point for the future, its message is that we’re on the right track, and it proves that it’s possible to work with these tools.

Á. P.: Attila is going to direct Az ember tragédiája (The Tragedy of Man) again, perhaps for the fifth time, I don’t even know. This drama, which is considered a mystery play by many, raises the most important philosophical questions at the same high level, and has faith as the foundation of the entire work in the same way as the Passion of Christ. We’re very curious to see how it will turn out and how the experience of staging the Csíksomlyói passió will be reflected in this production. Attila Vidnyánszky ‘s direction of Bánk Bán was also remarkable: the approach to the chronological structure, the epilogue beyond death in the performance already pointed in the same direction as the Csíksomlyói Passió. We can talk about a unified directorial perspective here, an apocalyptic worldview which is not at all alien to the postmodern toolkit. Years ago, when we started talking about the end of the postmodern era in sight, he said: “But I thought I was a postmodern director”. The Russian school in which he was raised seems by every indication to carry a completely different perspective and is closer to what we tried to talk about earlier, that postmodernism does not necessarily mean a radical departure from Christian foundations. The interpreters of postmodernism in our country do not yet want to see that the same process is taking place behind the new phenomena which they have taken into account; that we’re getting closer to the moment of Libra, the Scales, which is none other than the dramatic situation of the last judgment. Once my students asked me when I thought the final judgment would come. And then suddenly, because at such times one is forced to respond spontaneously, I found myself saying that we go through this moment several times a day, we just haven’t stepped into the centre yet, and so the balance is still tipping back and forth. That’s one reason why our stories are not written in a linear chronological order but often in reverse time structure, and why that particular “fragmentary dramaturgy” appears on Attila Vidnyánszky’s stage, composing and reinterpreting the dramatic plot in a way that diverges from the usual logic…

Translated by Nóra Durkó)

[1] The adaptation of Imre Katona’s Passió magyar versekben, avagy a megfeszítés története (Passion in Hungarian Poems or the Story of the Crucifixion), which was presented at the Egyetemi Színpad (University Stage) in 1971 under the direction of József Ruszt, was based on Árpád Fülöp’s collection published in 1987, which comprised only four school dramas. The same source was used by Elemér Balogh and Imre Kerényi when they staged the Csíksomlyói passió (Passion Play of Csíksomlyó) at the Várszínház (Castle Theatre) ten years later.

[2] Medgyesy S. Norbert: A csíksomlyói ferences hagyomány forrásai, művelődés- és lelkiségtörténeti háttere, PPKE, Bölcsészettudományi Kar – Magyarok Nagyasszonya Ferences Rendtartomány, Piliscsaba – Budapest, 2009

[3] Ferences iskoladrámák I. Csíksomlyói passiójátékok 1721–1739. Szerk., s. a. r.: Demeter Júlia, Kilián István, Pintér Márta Zsuzsanna. Argumentum Kiadó – Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2009 (Régi Magyar Drámai Emlékek [RMDE] XVIII. század, 6/1.)

[4] Erdélyi Zsuzsanna: Múltunk íratlan lírája. Az archaikus népi imádságműfaj háttérvilága, Kalligram, Pozsony, 2015

[5] [translator’s note: in Hungarian the compounds “pénzváltó” (money changer) and “megváltó” (redeemer) have the same word as a second member (“váltó”), so there is tension arising from the overlap in form and the diametric contrast in meaning]